Considering my rebellious mood when I arrived back for Grade 12, I probably should have been more upset at being kicked off inside kitchen crew. Being on inside kitchen was about the best duty period job there was because you got to eat as much as you wanted. But the cook and I never seemed to get along so each time I was assigned to his crew, he always managed to get me removed.

Being appointed to the meat sales crew no doubt helped me get over the disappointment. Over the years I had come to enjoy meat selling and in a letter home, I was even able to make light of my dismissal.

`This year I started off on inside kitchen crew with the cook but again I was fired I imagine for incompetence. I rather liked it as it might have given me a chance to put on some weight. Now I'm on Mr. Byfield's sales crew.'

The irony, of course, was that in my mind he was the one lacking competence. It was an attitude that I’m sure did not help my case – hence my removal. On the other hand, I never doubted Mr. Byfield’s competence. He was a man overflowing with ideas and energy. Time and time again he proved it possible to accomplish the impossible, especially in the area of fundraising and meat-selling.

Working for him could be nerve-wracking, stressful, even brutal to one’s ego, but it was also very satisfying. My new assignment I knew would be one I would enjoy. He wanted me to develop and implement a new sales strategy. Four years earlier he had put me on the crew that came up with the school’s first meat-selling campaign.

Back in the fall of 1963, there had been less-than-satisfactory results using parents to sell our flocks of roasting birds. The school realized the operation had grown too big to be dependent on parents selling to their friends.

I and one other boy were given the task of organizing the names of previous buyers into city districts and adding potential customers using Anglican church parish lists. Each name, address, and phone number had to be entered on a card, then filed alphabetically according to the district and street.

Once the weekly sales campaign began the two of us, aided by others, would send out a mimeographed sales letter to names in a particular district prior to the Wednesday evening phone calls. Chickens would be delivered the following Saturday.

The new system worked like a charm. After four Wednesdays of selling in March and early April, we had sold the entire flock. The school made a profit of $2,000 on gross sales of about $6,000. I discovered I enjoyed the selling as much as the organizing. In one letter home I was able to boast a 50 percent success rate – selling 24 birds in 50 phone calls. For most of us, selling was almost fun, particularly because you got to go into Winnipeg for the evening.

Around 6:30 p.m. as many as 60 of us would take over the desks in the main office of either Great West Life, Imperial Oil, or Manitoba Telephone Commission depending on whose turn it was. For the next three hours, we would sweet-talk as many people as we could into buying our five- to six-pound roasting birds for 60 cents/lb.

The letter that had been sent out was a great conversation opener. They usually hadn’t read it but they were almost always willing to listen to a synopsis. And that would often lead to questions. At that point, the chicken (or chickens) was as good as sold, especially if you talked about raising them ourselves.

Like all salesmen, you’d experience slumps. But five calls was usually the longest you’d go without a sale. Just when you thought you had lost your touch, you’d hear a great line over the din of conversation around you and bingo, you’d have another sale.

“You say they’re too big for you and your husband. You should think about having a dinner party. Your guests will love our chicken!”

One of the perks was there was always time to call home or a girlfriend, neither of which was permitted at the school. After all, you might sell your mother or girlfriend a chicken. The school almost went overboard to ensure we liked selling. The hamburger and pop stop on the way home, either at Kavanagh’s or Salisbury House, was very popular.

In typical St. John’s fashion, however, just as the system was beginning to work well changes were made that disrupted things. By the following September not only had the size of the flock tripled to 6,000, but there were 70 Holsteins was ready for selling as ground beef, shanks, and roasts. I wasn’t involved in the organizational work that year but a dozen other boys were. From then on Henderson’s Street Directory became the backbone of the sales operation. Overnight every household in Winnipeg became a potential customer. Photocopied pages of the directory became our call list.

Deliveries became a nightmare because orders could include up to six items – ground beef at $.49/lb., beef shank at $.49/lb., blade pot roast at $.49/lb., cross rib roast at $.59/lb. and round steak roast at $.89/lb. Finding a roast of a specific weight was a lost cause and usually ignored.

The fall campaign began in mid-October in Fort Garry. Deliveries that Saturday took until midnight to complete. The problem of accurately matching deliveries to orders was never licked. When we gathered on December 11 at St. Matthew’s parish hall for a banquet to thank the many volunteers who had helped, nearly $20,000 worth of meat had been sold. By the end of the year the total had reached $40,000.

As for the delivery problem, it was solved by discontinuing the raising of beef. As the annual report noted that year, it was a decision that brought joy to the heart of the farmer next door since it was his garden and fields would no longer be a favourite destination of the herd.

The following fall it was back to selling chickens only and the system once again worked like clockwork. In my October 23 letter, I reported that after two weeks of selling there were only 600 birds left. My own accomplishment, twenty-three (23) chickens to seventeen (17) people, was greatly overshadowed that particular week by the school’s top salesman, Bill Ritchie, who sold 100 chickens in a single order. The purchaser happened to be the owner of the River Heights Mini-Mart!

An even bigger thank-you banquet was held that December, bringing together school supporters dating back to Day One of the part-time school. By the end of the spring sale, it was clear the program had become a success both administratively and financially. On gross sales of $32,000, a remarkable $10,000 was profit. It was beginning to look like the perfect sales program had been found.

Apparently not.

The school felt it was taking too much time each week, what with senior boys out selling Wednesday nights, doing call-backs Thursday nights, and junior boys delivering all day Saturday. There was also a belief that the dollar value of each sale could be boosted with a wider range of products. Beef might not have worked but supporters who were butchers assured the school that smoked pork products would.

To solve the time problem it was decided to eliminate phone sales and go door-to-door. That way the salesman also became the delivery man, greatly reducing the amount of time invested in each sale. The solution to the second problem was to get into meat smoking. And that meant making some 11th-hour modifications to the new building project that was underway.

By late October of my Grade 11 year, the first of many hundreds of pounds of pork sausages, bacon, and ham had come off the assembly in the school’s new meat room. The facility included a 320 square-foot refrigerator, a 180 square-foot freezer with a flash freeze unit, an electronically-controlled smokehouse, a sausage-making machine, and a variety of other equipment needed for butchering and packaging. A new duty period crew directed by Wayne Cooper was created to do the work. One important difference from the earlier attempt to diversify our product line was that we did not raise the pigs ourselves but instead bought sides of pork wholesale.

We hit the streets of Winnipeg with our new product line on the first Saturday of November. For the first time, the sales force was divided into teams of eight captained by Grade 12 boys. While there had been individual prizes for top salesmen in previous years this time team competition was tried.

The district that particular Saturday was divided into areas and the captains drew numbers to decide where they would get to go. The previous Saturday’s sales brochures had been dropped off by junior boys so most residents were aware we were coming, even if they had only looked at the pictures.

Of all the improvements the school made over the years, in my view none helped the salesman more than the introduction of the one-pound package of sausages for $1.50. Even if the person had just finished their weekly shopping, they were usually willing to buy at least one package.

Very quickly it became almost a game of cloak and dagger to make sure you didn’t run out of sausage before the day was over. Until the meat room was able to produce more than we could possibly sell in one week, a cloud of suspicion hung over those teams with consistently high sales.

That obviously included the team I was on, captained by Rick Montgomery since we had the highest sales three weeks in a row. I don’t think there was anything to justify the suspicions though I recall occasionally finding sausages in boxes marked something else. But knowing St. John’s, that was far more likely to be accidental than deliberate.

Finishing first each week was worth more in terms of the acclaim than for the free meal you won. That was because every team that sold an average of $100 per person also won a restaurant meal. The result was that most weeks, there was a parade of teams being driven into town for dinner at the Lord Selkirk Hotel. And any amount over $800 for the eight-man team could be applied the following week should sales fall below the mark.

One week we received a whopping $500 for a package of sausages. As my letter home relates that brought our total to $1,350. Another week when the captain was away we sold only $627, but the surplus from the previous week meant we still won a meal. I think we only missed a meal once that fall.

For three days prior to the Christmas holiday, we blanketed the city selling chickens and taking orders for Christmas hampers. The two-page brochure promised each hamper would contain:

`One 4-5 lb. St. John's ham, cured and smoked in the old-fashioned way One St. John's Cottage Roll One pound of St. John's sugar-cured back bacon One pound of St. John's side bacon Three pounds of St. John's pure pork sausage'

The hamper scheme turned out to be a huge success. With all of us away on holiday, the task of preparing the meat and delivering the hampers fell to the masters and their families. Even working 18 hours a day there were still 400 undelivered hampers by Christmas Eve. Remarkably, the remaining 400 customers agreed to take them as New Year’s hampers.

New teams were picked for the five-week sale in April, and though my reports home are not complete, the team I was on appears to have been far less successful. Not once do I mention going out for a free dinner. Overall, this was not the case with the campaign.

On the final Saturday, the Grade 12 class challenged the other grades to a contest. They were of course pretty confident of winning even though they were going up against classes with more than twice as many members. And when the counting was over it was they who sat down at the winner’s table, having sold a remarkable $1,300 worth of meat. My class had not been quite so highly motivated. We finished last with $600 in sales. The final tally for the year was just over $100,000, three times the previous year’s total.

The new sales project that Mr. Byfield wanted me to direct was basically a modification of the old phone sales system. The difference was it would operate on a daily basis using the school’s recently-installed direct line to Winnipeg.

Two things would be achieved: the meat room would now have a regular outlet for its products and there would be revenue from meat sales every week of term instead of just during the sales campaigns. Mr. Byfield soon got involved in another more urgent project, notably the opening of a second school, so the whole thing became my baby.

The biggest challenge turned out to be handling the sales force. They were all junior boys and they quickly stopped being intimidated by anything I said. The threat of being demoted to floor mopping or pot-scrubbing was about the only that got their attention. We were calling loyal customers for the most part and as a result, sales were pretty respectable.

The door-to-door campaign began in late October during which each Grade 12 student captained a sales team. The policy of free dinners for sales over $800 must have become too expensive because my letters home reported only the winning team each week got to dine out. For my team that happened only once when we sold $1,200 worth of meat in River Heights, the best sales district in the city.

I personally did well and was only beaten by Don Forfar for the individual sales title. The previous year, Don had won a jack knife but at the time he made it clear that he thought the prize should be something more substantial. In Grade 12, he got his wish and the school invited him to name his prize. His reply – a driver’s license. To his surprise, the school kept its promise. He was put on vehicle maintenance crew and by spring had a driver’s license.

During the spring sale, it was decided to expand the inter-class challenge. Grades were in competition throughout the campaign and the one with the highest overall average per person would be the winner. The prize was a dinner plus an extra free weekend – a prize sufficiently appealing to win a rave in my letter home.

Considering our showing in the grade competition the previous year the prospects for my class winning were not good. The animosities leftover from the canoe trip meant we were anything but united. A good example was the refusal of half the class to back Forfar in the student election for prime minister.

As it turned out we did work together and we did win. On the final Saturday, we even managed to round up several former class members including Jon Guy and Ron Churchill to help with deliveries. Our per-person average over the five weeks was $16 higher than the next nearest class – Grade 10. I personally sold an average of $110 for five weeks in a row, a figure that made me, if not the top salesman, close to it. Since I have no record or memory of winning a prize I assume I didn’t.

While sales for the year were only $82,000, $18,000 lower than the previous year, our adventures in the meat-selling business received national attention in February when Weekend Magazine featured on its cover a beaming Chris Jorgenson braiding sausages.

Inside, the story was anything but upbeat, portraying the school as a work camp for misfits. We may have lost a few meat customers over it but the story did wonders for enrollment. The next September the school had little difficulty finding another 100 students to open St. John’s School of Alberta outside Edmonton.

My stint as leader of the daily sales crew came to an end about the time we started the spring door-to-door campaign. Mr. Byfield had a new project – a massive clean-up of the property including the demolition and removal of the old dining room in preparation for Open House in June. I was needed as crew leader.

Richard de Candole has been working in British Columbia and Alberta as a reporter and editor for over 40 years. Toughest School in North America is about his five years as a student at St. John’s Cathedral Boys’ School in Selkirk, Manitoba from 1962 to 1968. Richard lives with his wife Wendy in Qualicum Beach, British Columbia.

Buy the book exclusively through Amazon.

Hi, during my time as a student, 72-75 we went meat selling once a week in 3 “campaigns”. Fall, winter and spring. Each lasted about 6 weeks, usually until all the chickens were gone. Sausages were $1.99 and back bacon 6oz for 99 cents or $1.99 a lb.i was never anything special as a salesmen but some classmates were.

In the spring of my grade 12 year our class had Mr. Weins as the driver and the prize was, of course, a restaurant meal. We ended up winning, but there is a back story.

One classmate was Wayne Leatherdale who was a 7 year veteran. His dad owned a funeral parlour business in Winnipeg and he was very involved in school activities. i seem to remember he purchased the remainder of our inventory a couple of times, pushing us over the top.

Frank chose the restaurant, and it was a small place in East Selkirk, run by an elderly Ukrainian couple, everything was homemade and better than most restaurants i have ever been to.

We were suppose to go to a movie afterwards, but since we were only 3 weeks from graduation it was decided to pick up some cases of beer with that money and go to Wayne’s dads house to drink it. Vern was a natural host and had a big basement with a pool table, fridge and his wife provided lots of snacks. We were even allowed to smoke!!!.

Hi Richard

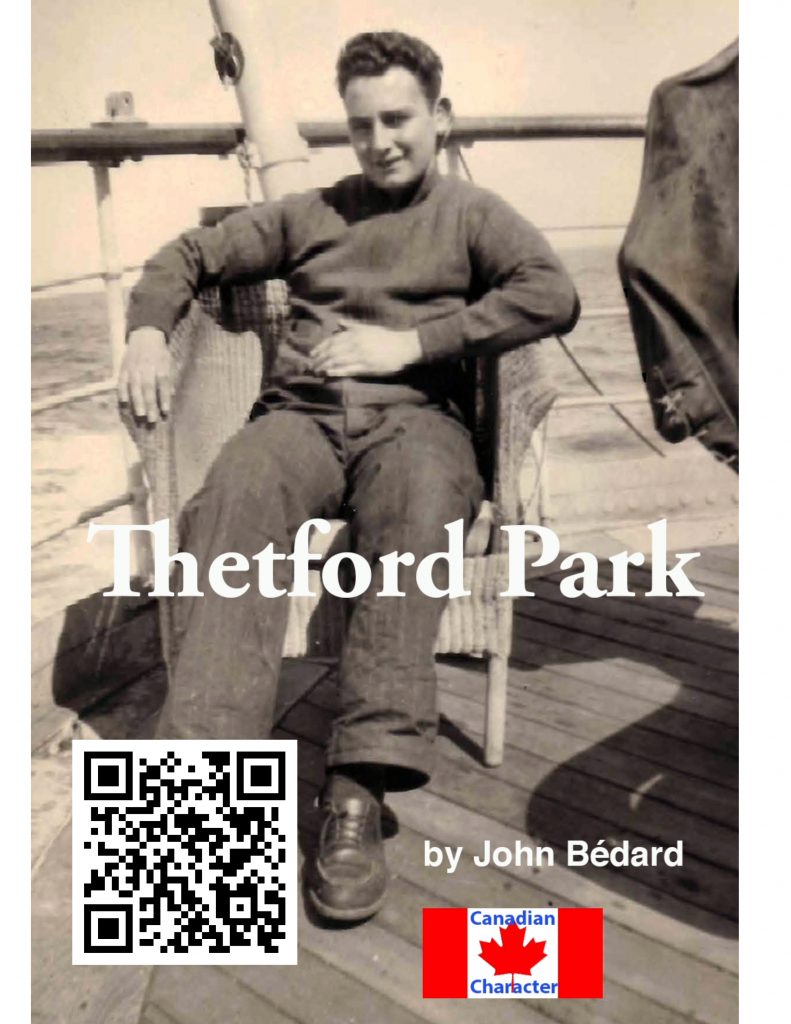

The picture at the lead of this story is of my mother Margaret Cormie at our house in Selkirk in 1966 or so. With her is Russell my grade 8 classmate. I don’t remember his first name. Mom was a strong supporter of the school and volunteered often . In this case it was to help promote the meat program.

David Cormie II

Thanks for the comment, David!