| Page length | 163 pages |

| Languages | English and Québecois |

| First publication | Dec 2013 kindle / Dec 2020 print |

Intro

la rive sud was first published in 2013 as Amabilis of Sainte Croix. It is the third book I’ve published. Written by my grandmother, known as Mumum, who was born in 1902. These are a Québecoise’s rural memoirs about a generation or so of people who lived from the late 19th to the mid 20th century, on the south shore, or “rive sud” of the St. Lawrence River.

Amabilis’s point of view and perspective is a fresh view into a turbulent piece of Québec history. She is simple. Her only allegiance is to her family.

Included in the 2020 edition is her complete original memoirs en québecois.

Why translate memoirs? To what end? They are incomplete, with gaping holes. They were written late in life and as many things are, in spurts. They rely on hearsay and the 20/20 of hindsight.

Amabilis is not historically important, though she touches people and events, like the Spanish Flu, wars, and the Beaudoins of Laurier Station.

I translated her work, her memoirs, because like Victor Hugo, she mattered. Mumum took the time to handwrite them out and my uncle Michel took the time to type up her handwritten notes, and I took the time to translate and adapt, so her words and my version of them, can live on in French and English.

People think the Québecois are French. We are not. We are North American. We are North American like Kerouac, rebelling against the dialectics of an old Europe which often relied more on predestination than talent for success.

There are many who crossed the border south to find fortune, and then just as quickly came back north. My maternal grandfather, Antonio Roy spent time in Manchester, New Hampshire, before returning to the asbestos mines of Thetford Mines, in the Eastern Townships of Québec. Amabilis’s father, Alexis Hébert, my great-grandfather, was forced to come back to Québec from the United States to take over the family farm on the death of his father. The man I was named after, my mother’s uncle, an Assumptionist brother, became a naturalized American citizen in the 1930s. When he died, he had three funerals north of the border, one after the other, and is buried in the Sillery district of Québec City, on a nice hill, with other Assumptionists.

My family gave up on Québec.

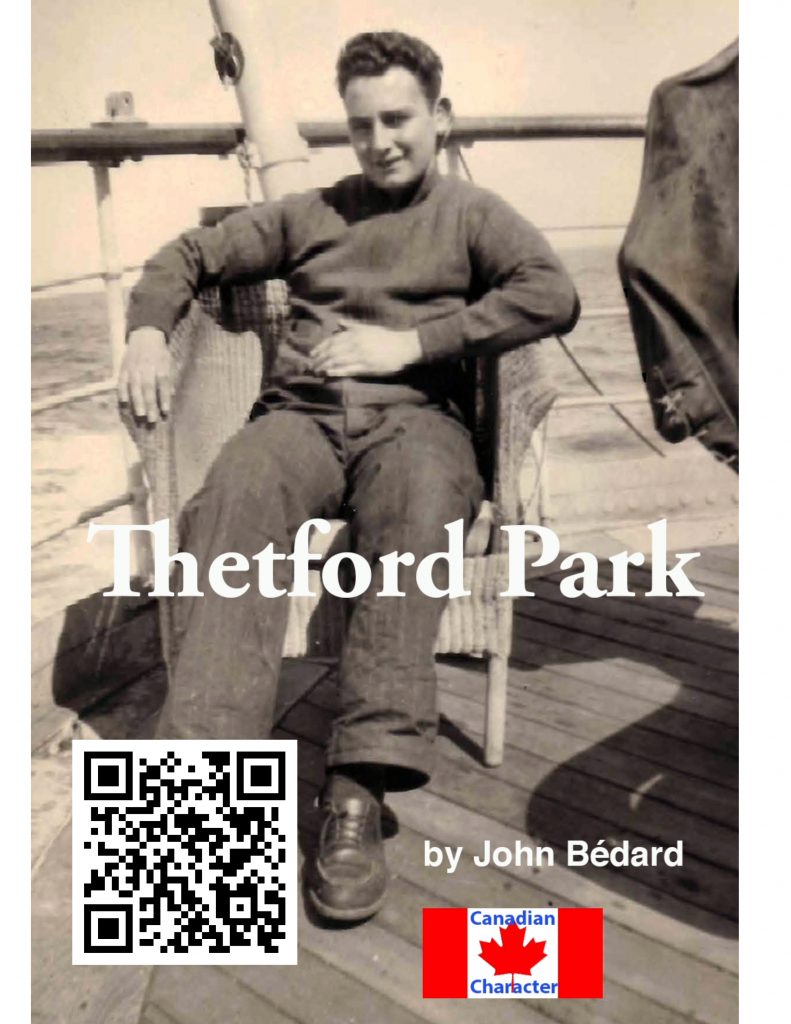

We immigrated to California from Québec in 1964 for economic opportunity. John had fought and he had sacrificed in both WWII and Korea – where was his piece of the tourtière, the life-sustaining Québecois meat pie? It wasn’t available in Montréal-Est. He was forty years old when we came to California.

As you read this, remember that my translation is an interpretation of Mumum’s interpretation of a past time. Slather on top of that my biases, my interweaving of timelines and people long dead who now live in the words, and this is what you get.

Her memoirs are for the most part measured, to the center, and generally empathetic and positive, unless we are talking about les Beaudoins. Laurent Beaudoin, his son, was a contemporary of my father’s and became CEO of Bombardier in 1979.

Plot

Is there a plot to a memoir? We all know how it’s going to end. We all know that it is about someone looking to the past, behind them, not ahead. The only plot is time’s little drips, lost in hot, humid afternoons turned into thunderstorms.

There is no plot to la rive sud — maybe just time and place that flowed past like the St. Lawrence below the cliffs. Amabilis Hébert Bédard, an agrarian québecoise of the 20th century born in 1902, grew up with the century and documented some of the key events from a unique, first-person perspective. It’s an analogy, an allegory to the St. Lawrence basin, to the hard water and soil.

Between 1899 and 1904, five Hébert girls were born to Marie Zelphida Hébert, née Charest. Between 1924 and 1946, these five Hébert girls in turn gave birth to sixty (60) full term babies.

Amarilda, the eldest, had fifteen (15), Ida, the next, born in 1901, sixteen (16). Amabilis, the writer of these memoirs had twelve (12), followed by Anne Marie with nine (9), and Juliette with eight (8).

The Author(s)

Amabilis Bédard. I spent many hours with my grandmother, Mumum — watching her bake potato bread, make chicken rice soup, wash dishes, read, and play cards, all on the South shore of the Saint Lawrence River – le Fleuve Saint Laurent – where her life was lived, a little more than 30 miles west of Québec City. She wrote out her memoir by hand.

Michel Bédard. Without Michel prodding his mother to put her memoirs down, to commit them to paper, we would never have them to translate. He took it upon himself to first make photocopies of her handwritten stories and distribute them to everyone. Later, he typed up the manuscript and shared it.

Translator

Pierre Bédard. I picked up the task, la tache, though in a very different and unexpected (or expected) direction, translating and adapting her writing and his efforts. At 19, I translated Victor Hugo’s Hernani into English, a significant play taught in many drama departments today. I’ve written/translated/channeled my many voices, my father, John, my grandmother, Amabilis, my uncle, Michel, and Victor Hugo.

Editors

Heidi Lepage. My dear cousin, my Mom’s godchild, another of Amabilis’ many grandchildren put together the French version so it can be included in la rive sud. Amabilis’ original texts solidify the historical significance of her first person observations of things like the Spanish Flu in 1919.

Jean-Pierre Bédard. It was a poignant edit for Jean-Pierre, a great-grandchild of Amabilis, as he lived through his great-great-grandfather Alexander’s losing battle with bladder cancer as he recovered himself from two surgeries in one year for thyroid cancer. Editing can be a brave act. I had trouble with some of these passages myself.

Writing Process

Everyone has a writing process. There’s always a story within the story. Michel Bédard, Amabilis’ son, persuaded her to write down her memoirs which he in turn typed. The memoir is in French, which opened up many possibilities for me from a “translation vs. adaptation” perspective. I translated the first version of la rive sud in a very linear fashion, from start to finish. The original French, edited by Michel Bédard and Heidi Lepage, is included in the kindle and print editions. En Quebecois.

Amabilis hand wrote the draft in what she did best, cursive. A schoolteacher by training, she enjoyed reading and writing, two activities to get everyone through tough times. Michel as she says in the first parts of the book persuaded her to put this stuff down, so she did.

First I translated. Being native Québecois helps, but there’s always enough ignorance to go around. Then, I reordered her writing so that it fell chronologically, grouping her memoir in a timeline. As I translated, I edited for my own perception of readability. Translation is adaptation to a great extent, and there is no shame in erring towards readability. Care was taken for fidelity, but an astute reader will find little ripples in the matrix of her memoirs as things were stitched together chronologically.

Scanning. Better living through scanning. With la rive sud, I went to Word from handwriting. I think I tried to keep the same thread Amabilis kept, but it soon became clear that there really wasn’t that much of a thread to her story — she had Kerouaced her memoirs — much of it was stream of consciousness. But brilliant.

Nevertheless, I needed a thread, because everyone needs a thread, and my grandmother, Amabilis, as much as I loved her, was not Victor Hugo – I could mess with her timeline and she would likely approve.

I started this book with my Uncle Michel’s manuscript, which was a typed version of Amabilis’ memoirs. Over time, I also procured her handwritten input for backup and reference.

I spent a good amount of time with Amabilis, in a chalet sitting on the St. Lawrence in St. Croix, essentially hanging out. We played all sorts of cards, as a ritual.

Card games are excellent icebreakers. Especially if you play trying to cheat (or gain the advantage) over your opponent. The embarrassment of getting caught was overcome by the celebration of her mental acuity. It seems odd, now that I approach the age she was when I first met her, but that’s how the world works. It is a circle.

One game we played together (or alone) was patience — known to the English-speaking world as solitaire. I spent enough time with my grandmother to be inspired to keep going with it.

Factoids

Timeline. At first, I was going to leave Amabilis’s manuscript “as is” in terms of sequence but I’ve put together some timeline coherence in the narrative. I’ve also grouped her thoughts into small chapters, as I saw fit. What I strive for is not a literal translation, or validation of what is written, but the story. Interpretation; not translation. My thoughts are expressed as footnotes.

I’ve translated and adapted her work for readability and have included the original source French document as the last chapter of this book. In this way, at the very least this book serves as a bilingual historical record of Amabilis Bédard’s musings about life in the early 20th century.

If you do read French, you can grip whatever sentiment translation often fails to capture in the original Québecois. You get her point of view of events and her voice. I don’t bring it to life, it’s there already.

Cats and dogs. Only one part of the book remains in the French version but not in the English, and that has to do Quebec’s animal control regime in the mid-20th century. There wasn’t any and it was a very cruel world. The prevailing attitude during the Depression era about cats and dogs and animal control does not stand the test of time.

English – the path to liberation. My maternal grandfather, Antonio and grandmother, Emerentienne, were both bilingual. It elevated them and ensured their survival. They became the buffer to the English overlords at the time, the way things no doubt got done. You had to learn to beat the devil at their own game. The English owned the asbestos mines, the Quebecois worked the pits and tunnels, and someone had to be the buffer. English was the key, and in many ways, it still is key to economic survival.

Themes. There are all sorts of themes packed into her memoir. The Klondike, lumberjacking, the onset of the Grand Trunk railroad, the movement to the United States, the Spanish Flu, and the wars, are all here from her perspective.

French and English under one cover. Like Québec itself, la rive sud is a hot mess of lives described one paragraph at a time during hours stolen from the day. Included in the edition is Amabilis’ complete original memoirs en français, edited by a granddaughter, Heidi Lepage. I thought it important to add if anyone wanted to figure out what I did to her words, but also, to get the original sense of her words in French. The story opens with a family, the Poulins, selling everything to move South.

Le feu. The fire that occurred in August of 1936 devastated the Bedards. It was at the tail end of the Great Depression. My father was 12, old enough to suffer it, and surely expected to grow up quickly as a result of the tragedy. John would always tell us “not to burn the house down.” Reading about the fire, we know why.

Poverty. Hunger characterized much of the early 20th century. Québec was not immune. One of the true social justice pioneers, Pere Brousseau, built a commune of sorts for the old and infirm – people with no place to go who would literally be thrown out of the house, in Saint Damien. Amabilis attended the school and documents it, including a fascinating passage about surviving the 1919 pandemic at the school. Her words sparse, but still history.

What I’ve written is a wrapper around her memoir, my opinion, as her grandson but also as an historian and linguist, about what really went on. It’s first person, which is the best person.

Letters. The writing and delivery of letters seemed to dictate the tempo of the day — mail call. You lived or died by what the post brought, No one was desensitized information, by the constant bombardment of information. Mail came once a day. If lucky. Damn lucky.

I have some original letters from Canada to California written to my parents in the mid-’60s, and every space is filled with writing, to minimize the time spent with the subject. To minimize the postage, to keep it to the cheapest airmail rate — you didn’t want it returned weeks later for insufficient postage.

Writing a memoir. It was never my intent to have or to create a salable product. It’s my intention to create a readable and enjoyable product meant to live on. Meant to be picked up and read.

Happiness. What was the definition of happiness? A full stomach. A warm bed. Not dying of bladder cancer? Not losing a toddler who gets too close to a flooded creek? The ultimate embodiment of happiness seems to be survival. Yes, different themes and ideas come and go, but a good meal at a table seems to be integral.

Amabilis lived and saw her share of misery and tragedy. she was lucky to survive all the births and to only lose one child. She lives through her children and is happy to do so.

All in all, happiness, for Amabilis, is a job well done, a solitaire game solved.

Mumum would approve. That’s why I translated la rive sud. She lives. Amabilis lives.

Deep down, I felt that if my grandmother had taken the time to get her thoughts down, and my uncle had taken the first cut at organizing the mess of it, then I could certainly rewrite it (after translation).

Motive is supposed to explain something, but I really can’t. Like much of what we do, I was driven to it by some unknown. It was not my idea. It wasn’t as easy to establish chronology as you would think. I had to fill in holes. I researched an eclipse. An earthquake.

The terrible fire which destroyed the family house and store in Laurier Station changed the Bedards forever. That night, the family fortunes took a downturn as Delphis, her husband, was never able to start up the store again, because of the salaud (Amabilis’ word, not mine) Beaudoin.

Beaudoin’s son went on to marry into the Bombardier family and run the firm. The fortunes of one night. It’s passages like this that make history, history.

I gave the book oxygen on the web, serializing the chapters. It gave me another chance to rewrite the book. When I was young, I would cheat Amabilis at cards to make sure she was still with it. She caught me every time. It was embarrassing. Always on double solitaire. People then kept busy playing cards and writing letters, if they had anyone at all to write to — it was the rage.

When I rewrote la rive sud, I chunked out the chapters, and laid them out on a card table, mixing and matching, seeing what glue had to be written. And so it went.