Pop always wanted me to be CIA.

For a few hours in 1973, he got his wish.

Air America was an American airline covertly owned and run by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) from 1950 to 1976.

The United States Customs Service was founded in 1789 to collect tariffs, stop the smuggling of illegal goods, and greet people at border ports of entry. Subsumed into the Department of Homeland Security in 2003, the Customs Service ceased to exist.

Richard Nixon

Even before John Bedard joined the United States Customs Service, before he was even a citizen, he proposed to Richard Nixon via letter, cc’ed to the Orange County Register, a scheme which eventually became known as Operation Intercept. And so John Bedard, an immigrant and freshly minted US citizen who had served nine years working for Canadian Immigration before moving his family to Orange County when he was 40 years old, may well have made his future by writing this letter.

Operation Intercept shut down the Mexican border. Every car going through the line at San Ysidro was inspected thoroughly, backing traffic up to Ensenada. Secondary control became the world’s biggest vehicle chop shop as cars were field stripped by US Customs agents and left for their owners to put back together, if no contraband (including paraphernalia . . . a roach clip . . . a roach) was found.

Operation Intercept was an absolute disaster, a mess. People could not live with the wait times at the border — many lived in Tijuana and worked in San Diego and they needed to get to work. The Tijuana/San Diego metroplex was beginning to flex its muscle. The sheer audacity of shutting down the port was frightening and insane. It ended almost as fast as it started, but not before gaining my father employment as the US Customs Service expanded its drug interdiction role. His hiring into the Customs Service was tied to the ever-growing need for inspectors.

John applied for employment as soon as he became a US citizen, which was the one job requirement time solved. While a rookie to the service, he had his years with Canada Immigration, and was fluent in French, English, Spanish. He was learning Russian and could swear in Yiddish. He was a hot commodity.

Shortly after joining US Customs, Inspector Bedard applied and was accepted for a posting in Laos, working as an advisor to the Royal Lao Douanes, their customs service. John was part of a small team of advisors. He was assigned the south of Laos, ranging from Vientiane down to Cambodia – mainly along the Mekong River, a natural border and smuggler’s paradise, the border between Thailand and Laos. Drug interdiction was only one part of the mission. Training personnel and setting up schemas and procedures for the collection of customs duties was just as important. If something can be carried across a border, it can be smuggled, and it often was.

Drug interdiction in Laos became a national priority for the United States, especially in the north, in the region called the Golden Triangle, defined by the area where the borders of Laos, Burma (now Myanmar), and Thailand converge. The Golden Triangle’s heroin was flooding the United States, the region’s poppies yielding heroin which was on par with Afghanistan’s quality.

1972

The year 1972 found the family in Laos, living in a war zone, not a bone spur shared between the four of us. We were fresh Americans, recently naturalized citizens. My Aunt Celine wondered if we would return in body bags, one for each of us — my father, John, mom, Therese, brother, Marc, and I. Each monogrammed (pdb for me).

The reality was much different from the fear. For an adolescent, Laos could be the most boring place on earth. We did not belong — we were not “career” USAID, State Department, CIA, nor Air America. My parents had more affinity with the French expats left over from the ancien regime and Canadian Oblates doing missionary work, than they had with most of the American community.

I was 14 going on 15, and my time in country was coming to a forced end as I was getting sent off to boarding school in Manitoba, coerced by the promise of a summer spent in Quebec.

My uncle was getting married in June, and I was to represent the family. The tickets had been bought weeks ago and the thick, narrow rectangular packet sat in my mother’s dresser drawer, with all the other important things. Timeliness, and time itself, had different meanings in 1972.

Planning this type of voyage in a world of postage for business took time, patience, and oddly, planning, often not in that order. Summer in Quebec was the hook to me buying off on a solid year of exile from the family, not seeing or speaking with any of them until they made it back from Laos alive. After a year in Laos, I was ready for anything, though I didn’t realize then, nor could I ever imagine what it was like to not communicate except by mail, for 14 months.

Flying an Air France 747 from Bangkok to New Delhi, to Tehran, to Tel Aviv, to Paris, and then to Montreal required a ticket and its two carbon copies attached, for each leg. And then there was the flight alone from Vientiane to Bangkok the day before, to make sure I didn’t miss my Air France flight the next day. I wore my brand new Seiko watch that my parents had given me, which I would forget in a Paris Orly bathroom after washing my hands, and a three hundred dollar roll of American Express traveler’s cheques.

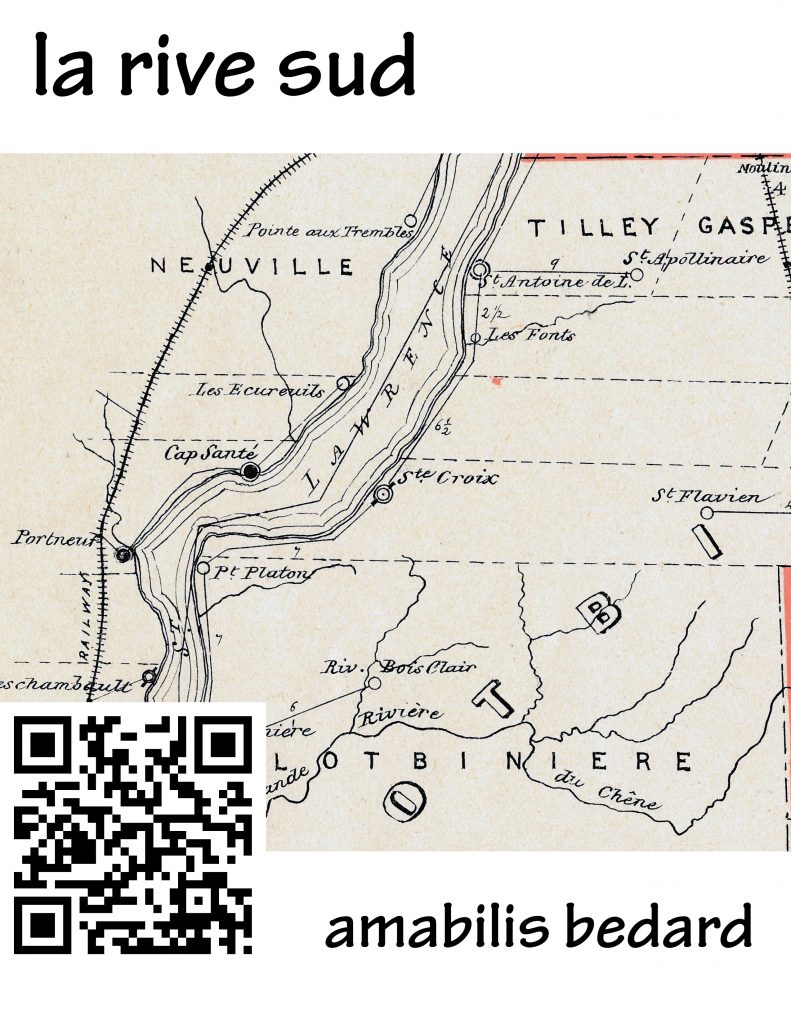

True to the gods of the US Mail, the APO, and Canada Post, the letter announcing my arrival at Dorval in Montreal arrived one day after me, panicking the Bedards who began a frantic search for p’tit Pierre, le gars de Jean as soon as the letter arrived in Ste-Croix, 150 miles away from Montreal.

I was headed back to Quebec and Canada nine years after we had left for Southern California, an American and no longer legally a Canadian. Until 1977 taking on another citizenship meant renouncing your Canadian citizenship. There were people called “Lost Canadians” caught up in the citizenship issues caused by the 1977 law. People suddenly discovered that they had never been Canadian, even though they had lived their lives thinking they were Canadian.

The truth was, I was being sent out of country before something bad happened. My father’s career in law enforcement would take a hit if his idiot son did something, well, idiotic. Being at the wrong place at the wrong time might require the family to pack and leave Laos within 24 hours, resulting in the termination of the US Customs post my Father had so fought to get. My adolescent needs, such as they were, could wait and be channeled on another continent at St. John’s Cathedral Boys’ School in Selkirk, Manitoba, allegedly the toughest school in North America according to the Knights of Columbus magazine. The headline had been used against me. My Father flashed the cover at me as I wallowed in the gutter of boredom. I was vulnerable.

“Want to go to school here?” my father asked.

“Whatever.” I said, or the 1972 moral equivalent of “whatever.”

A few letters from Pop to the headmaster and a deposit sealed my fate shortly. I was headed to Manitoba for my 10th grade, or my Grade 10, depending on your perspective.

When my father joined US Customs, we never saw him much. He was often on assignment or assignment, somewhere other than where we were in Orange County, California. When he was away, my brother and I did our best to torture our mother.

This changed when we went to Laos, at least for a little over a year. Laos brought the family back closer together briefly, until they decided to send me away. Of course, this never prevented Pop from going to Cambodia, carrying his expired Canadian passport, just in case.

Bone Spurs

What the hell were we doing there? Why Laos? The pulse of the war in Laos was dictated by the traffic coursing its way south on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The trail was a wonder of engineering and ingenuity. For years, the United States tried to neutralize traffic on the trail, dropping a bomb every seven minutes. The trail did not define the border – it played with it. Part of the trail was in Laos; part of it was in Vietnam. Rather than one big artery as the name implies, it was a series of intertwined veins, some coursing south, some north.

Laos was sort of Vietnam, without being Vietnam. If anything the War spilled over along the track of the Ho Chi Minh trail. We were an outpost, and there existed a legal fiction that it was a neutral country, buffering Thailand – sheltering the Thai from Vietnamese communist aggression. The Domino Theory, the theory that one country after another would fall to the communists from China south, just like dominoes, was on everyone’s top of mind.

In 1972, the domino was being stopped in South Korea and Thailand. It was as if Nixon, then Ford, and America itself decided to withdraw south of the Mekong by 1975, abandoning Laos and Cambodia. Unsustainable, it was coming to an end.

The four of us, as a family for the first time in years, were together in Vientiane, Laos a city in a war zone, sort of. There were three parties in Laos – the Royalists, the Neutralists, and the Pathet Lao – the communists. The United States supported the first two, the Chinese, Russians, and Vietnamese supported the Pathet Lao. Now it might seem easy to lump all three communist countries together, but the reality was that the Chinese and Vietnamese fought, and the Soviets and Chinese, though kindred in affiliation, engaged in their own regional competitions.

It was complex, but if you stayed within the city limits of the population center, Vientiane, you were likely safe. However pacific Laos all might seem, it was easy to be at the wrong place at the wrong time. Control of the country was always in doubt and had to be asserted, though sometimes more symbolically and through osmosis.

Howard Dean’s brother had been kidnaped and killed by the Pathet Lao while only fifty kilometers outside of Vientiane – very close to the population base yet very far. His death was likely a mistake. The Pathet Lao tended to be much more disciplined. He may have run into village justice as opposed to communist fervor. As a rule, the Pathet Lao did not go through Vientiane terrorizing the Americans. That came for later and much more anecdotally and passive aggressively. After the war, Laos did not reach Cambodian levels of violence and genocide. When the end came, what large cities existed in Laos were not emptied into the countryside like Phnom Penh, though the Hmong in the highlands and the Plain of Jars suffered a tragic diaspora.

While the large cities saw some violence, it was often more symbolic than the raw, doctrinal Viet Cong or NVA quest to liberate. The game was up in Laos. Most people knew it. The communists gained control as much by osmosis as by any other method. The land today remains scarred by American bombs and bomblets.

The day I left Laos was the day the Pathet Lao showed up at Vientiane’s Wattay Airport from Hanoi. The group of cadres sat quietly, all dressed in black slacks, white cotton shirts, and flip flops, on benches placed against the wall of the terminal. Their discipline only highlighted the insanity.

As I left, they came. It was subtle irony, given that some of my friends ended up in a bar fight with some Pathet Lao soldiers, forcing their families to undergo the diaspora of shame from whatever agency their families served.

We were going to avoid all that in my family.

VTE (Vientiane) to ZVK (Savanakkhet)

But I still had to survive through the end of the school year, and Easter week was here. It was the last school break before my long flight to Montreal, and my parents shuddered thinking about how to keep me occupied for a week. My fate was well-determined by then, but it still wasn’t safe. I may have been headed to boarding school in Selkirk, Manitoba via Ste-Croix, PQ for the summer, but it wasn’t safe.

My parents could no longer risk my impertinence, my lip, my ability to say wrong things at the wrong time, so staying in-country was out of the question. No one wanted only 24 hours to pack up to leave the country. No amount of pull from the Ambassador, nothing short of blackmail and extortion could keep your family in-country if someone strayed.

So it was decided that I stay with my Father in Savanakkhet, south of Vientiane on the Mekong. Off I went to hang out with Pop before my Mom killed me.

I flew to Savanakkhet on Royal Air Lao, on the airline’s one large four-engine turboprop still flying. The Lockheed Electra was the most modern airframe flown by Royal Air Lao – they needed it for their Vientiane / Hong Kong route. The whole family had taken this very plane to Hong Kong over Christmas for Rest and Recreation. I visited the pilot, who was a friend’s father, and sat in the cockpit jump seat while flying over South Vietnam at a very safe cruising altitude.

On February 11, 1972, a Royal Air Lao DC-4 flying from Savanakkhet to Vientiane disappeared, never to be found. It was presumed to be shot down with all 23 souls lost, but it might have easily been a navigational error given the ups and downs of all the transmitters at the various locations throughout Laos called Lima Sites. These locations housed transmitters and beacons, but nothing was set in stone and you had to pay attention to survive, especially with all the electronic spoofing going on out of the Thai airbases by American radar jamming aircraft. Some Lima sites were overrun by the North Vietnamese Army (NVA). Other Lima sites might just run out of batteries. Or a maybe a radio tube blew.

Royal Air Lao was not always a reliable means of transportation. If you had a choice, you flew Air America or Continental Air Services – you stayed away from Royal Air Lao. In my time in Laos, I flew Royal Air Lao twice, but Air America at least two to three dozen times.

Laos was a country of bad weather and otherworldly terrain. Navigation and the ability to fly by the seat of your pants were paramount if you were to survive a season flying. Navigation waypoints were key — it really helped to know where you were, especially where borders and disputed territories were concerned.

The Lao weather — hot and humid as hell, even this early in the morning — was beaten down by the plane’s air conditioning system. I likely guzzled down an ice-cold Coke once seated and offered one. As a North American, living in Southeast Asia, you had to stay away from the things which could kill you, like bacteria and other waterborne horrors. To survive Laos, all water had to be boiled. Not just brought to a boil, but boiled for a good ten minutes. Every household always had water on the boil.

The flight was short, long enough for a Coke. My Dad met me at the foot of the airstairs and walked with me away from the Electra, towards a shack, the Air America’s dispatcher’s office. In those days, you could pretty much wander around everywhere if you looked like you somehow belonged, and being American, this was one place we belonged.

Having said that, you had to beware when walking around an active airfield. One of the Air America Twin Otter pilots was nicknamed Dirty Harry – people kept walking into his propellors, which was really a mess for everyone concerned, especially the victim and mechanic tasked with cleaning the engine.

So here I was with my Dad, in the morning, on the tarmac in someplace so far away from home I just didn’t know where home was anymore. I sensed something – I got the feeling he was flying out for the day to a place where I could not be and that we wouldn’t be together much.

Pop was tense and on edge. He was working that morning. He didn’t really know what to do with me that day, as if I was unexpected. It was early and the asphalt in the tarmac felt like it had never cooled off from the night before. Who is going to do him the favor of hanging out with his 15-year-old kid? That’s a big favor.

I was slated to stay at a friend’s house for a few nights, but I was supposed to be with Pop all day. The only American School was up in Vientiane, so many kids boarded in Vientiane and flew home to Savanakkhet on the weekends. My buddy, Hubert, and I played baseball on the same team. His father worked for USAID. Everyone worked for USAID, the United States Agency for International Development. USAID was everywhere.

What to do with a kid with nothing to do, on the tarmac of an airport when you’ve got to run off to meet someone who doesn’t need to know that your son exists?

The Twenty

My father reached into his pocket and pulled out a small tight roll of American dollars. “Here,” he said, peeling one off, “This twenty should last you for the day. Bob and Sal here in this helicopter are headed to Pakse. Go with them. You guys will be back tonight.”

I questioned nothing as I walked over to meet the pilot. He was doing a walk around of the Sikorsky, performing what must have been his preflight check. We all shook hands. Bob and Sal had strong grips.

My mind started racing around things fourteen year olds think about. I wondered exactly how we would take off. I had never flown in a helicopter. Did they use the runway? Did we taxi? So many questions.

Bob and Sal. I had overheard that the First Officer’s name was Sal Canyon. I didn’t get Bob’s full name. I wondered if he was related to the infamous Dirty Harry, the Air America man, the legend, who flew Twin Otters. Probably not. I walked looking everywhere in an abundance of caution.

“See you soon, Dad.”

“Yup.” His safari suit kept its crease as he walked off.

To be very clear, my father gave me twenty dollars and packed me off in an Air America helicopter headed south to Pakse for the day, just to get me out of his hair.

What could I say? I couldn’t say I felt unwanted. I was as game as anyone else and had no issue with risk and adventure. As a freshly minted American, I was not bound by the norms expected. No one discouraged me from being stupid, stumbling into fantastic opportunities to learn something new. Such as the time I took a date to see The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly in Lao, with Thai subtitles. We were the only white people — falangs — foreigners in a packed theater. Didn’t matter, everyone loved Clint Eastwood.

Or, when I took French at the Lycée, and the only other non-Lao was the French teacher, who was fulfilling his French national service in Laos. He pleasured in making me squirm about the American bombing in front of his forty or so students. Pleas that I was an illiterate Quebecois went unheard. I couldn’t hide.

He would dictate passages for us to write down — la dictation – Montaigne, Diderot, and Pascal passages, with snippets interspersed about B-52 bombing strikes.

These are things you need to live through to feel how others live in societies foreign to your own comfort. All humbling experiences, forced to survive in a position of being the absolute minority. Necessary experience if you want to know how others live. You must learn to respect views beyond your own if you hope to survive.

I was bored and the prospect of having flown down to Savanakkhet for nothing was just one more boring thing in a long line of boredom. Going to Pakse for the day was additive.

I was game for anything. I took my father’s twenty and hustled off with Bob and Sal, taking care not to run into a wayward prop.

ZVK to Pakse (PKZ)

I was the only passenger (or cargo as you will) on the Sikorsky for the forty-five-minute flight to Pakse. The Sikorsky H-34 was the not-so-sexy workhorse in Southeast Asia. Remember the helicopters in Apocalypse Now? They were not H-34’s. When people think Vietnam -era helicopters, they think of the Huey. The H-34 took a different approach. It was a little slower, bigger, and could haul more cargo. The helicopter was a dependable workhorse. Some are still in use today, hauling air conditioning units up to the top floors of buildings.

Sal Canyon handed me a helmet with a built-in headset and I put it on. It was heavy, hard, and protective and felt good, like I was part of the crew. Only the best stereos available at the time had this type of get-up. And there was a mike, too. I could push the button and get heard by the crew or just sit back and listen to everyone’s chatter.

“Clearance, H-Eleven to Pak-Say.”

No answer.

“Clearance, H-Eleven to Pakse.”

Static.

“H-Eleven cleared to Pakse, three thousand VFR, depart runway 22, squawk 0-4-5-5.”

“H-Eleven cleared to Pakse, three thousand VFR, departing runway 22, squawk 0-4-5-5.”

“H-Eleven, read back correct. Contact Savannakhet Tower.”

Life was suddenly not so boring.

“Tower, it’s H-Eleven with you going to 22.”

“H-Eleven taxi to 22..”

We puttered to the edge of Runway 22.

“Tower, H-Eleven at 22. Ready.”

“H One One, cleared for takeoff, Runway 22, good day.”

“Tower, H One One, cleared for takeoff from 22, good day.”

Pakse was close; up, over the Mekong into Thailand, back over the Mekong into Laos, and down into Pakse Airport. All in a half hour or so. You head south, overflying safe Thai airspace at about 3,000 feet VFR, and then cut over the Mekong into Pakse Airport.

So I listened to the chatter as we taxied to the runway and lined up, just like an airplane. We sputtered to get there, burping slowly into position and the engine kicked in and we lift out and out of Savannakhet Airport. The green humidity below fell away.

How Bob and/or Sal knew my Father, I never asked. I suppose he was a frequent client going up and down the Mekong. It was rumored he traveled into Cambodia using his Canadian passport. It wasn’t wise to ask too many questions in these times.

We chugged up to our cruise altitude, about 3,000 feet. Below me was a flat landscape of orderly rice paddies — we were flying over Thailand.

Thailand was safer than Laos. All the pilots feared the magic bullet, the random potshot or little beebee that would bring your fine equipment down into the jungle — into the nearest clearing you can find as you trade altitude for speed while putting out a Mayday squawk, hoping someone can triangulate your coordinates after you go down.

Magic bullets only worked in Laos. Thailand was safe.

“No reason to be on the Lao side of the Mekong if we don’t need to be quite yet.”

“So what time are you coming back today? How long do I need to hang out in the club?”

Bob seemed like a pilot who never got to fly enough. We cruised with no turbulence. It felt as if the helicopter was just grabbing pieces of sky as we moved forward.

I expected to hop back a flight with them that day after scarfing down a sandwich. This is a milk run, right? My Dad had made me think that this was a milk run, that you were headed back later today.

We crossed the Mekong back into Laos and into Pakse. The Mekong meant safety. It was wide and dirty with runoff — powerful, like the St. Lawrence River, a fleuve, a powerful, going all the way to the sea, touching everyone in its path. The Mekong is a Mississippi of a river.

“Negatory, young man. We are on a three-day deployment.”

Awkward silence is what it is called. Three-day deployment? Holy shit, I thought it was a three-hour cruise, not the whole TV series.

“Three days, eh?”

“Three days. Then we rotate back to Udorn.”

Udorn, Thailand was the nest of Air America, the headquarters a few klicks over the Thai border. We would fly into Udorn to shop at the PX for things you just could not find in Laos. We would sit in C-123s in webbed seats against the walls of the aircraft. When the engines revved up for takeoff, you were in a box of marbles — the powerful engines vibrated everything. You could not hear yourself talking — all conversation ceased. Even yelling failed. They kept the back open so we could see the ground disappear below us as we took off.

I sat back to the vibration of the helicopter and accepted the uncertainty of not knowing how I was getting back up north. Might as well enjoy the quality time and my first ride in a helicopter on an airline that didn’t exist.

Bob and Sal were going to become the best of buddies flying in and about the Pakse area for the next three days, doing whatever needs to be done, whatever task dispatch sends their way as they operate out of Pakse. If you loved to fly, Air America was the place to be in 1973. Not only did they fly multiple types of aircraft, you got to do things which the FAA would not approve of, land on strips which were just that, strips of dirt carved into the side of a mountain. While the cities sat in plains, the outskirts were ringed by rough, raw mountains out of elvish fantasy novels populated by hill people, the Hmong, many of whom died or ended up in Minnesota and Wisconsin, resettled Americans.

“What do you do if you are being shot at?”

I knew that these guys were under fire all the time as a consequence of flying for Air America. If they were flying in Laos, they were involved in all sorts of hijinks, they had been shot at in the past and somehow managed to dodge the magic bullet that was headed every American aviator’s way who flew in Laos to fly another day.

“So, what do you do if you are getting shot at? How do you land?”

“Say what? Hold on a sec.”

“Pakse Tower, H Eleven, H One One, is ten miles out on visual runway one one.”

“H One One altimeter is 30.05.”

“30.05, H One One.”

“H One One is cleared to land runway one one, winds 180 at 5 to 10.”

And so, Bob got our clearance into Pakse.

“I said — how do you land if you are getting shot at?”

“Oh. OK. Watch this.”

Autorotation is often used in case of engine failure. You can freewheel down to the ground and try to have somewhat of a controlled crash. It’s the helicopter equivalent of gliding. Imagine the engine just disengaging. We must have been around 3,000 feet up off just off the airport apron.

I felt the engines let go a little as Bob took power off the throttle, to an idle. It suddenly became very quiet. We hung in the air and I felt a huge rush of damp, hot air come into the helicopter through the open crew door as we started down. Buffeted and no longer bored, I stared out the open side door as the ground floated up to meet us. My seatbelt was on.

As we came over the runway at around 200 feet, Bob applied full power to the engine and we landed like a bloody Cessna, as if the Sikorsky was a fixed-wing aircraft, straight down the length of the runway, slowed down, taxied, and parked.

I was impressed and profusely and profanely thanked Bob and Sal for the hop down to Pakse. Now it was time to find a flight home.

Tuna Sandwich

There was only one thing I ate when I was in Laos which was always safe and always available in an American-run establishment — grilled tuna sandwich, fries, Coke. Tuna and Coke come from a can, bread from a bag, fries frozen until deep-fried in oil, you get the idea. Avoid water and its hidden universes of bacteria and stay alive. You never know about the burger, everyone posited it might be water buffalo, but you knew the tuna came from a can.

I loved eating in the Air America clubs. It was never bad, or I was so easy to please that I accepted anything toasted served with a cold Coke (without ice). I would rather take a swig of lao lao (a potent, rotgut Lao domestic whiskey) than a sip of anything with an ice cube in it. We maintained a very strict regimen when it came to eating and drinking.

To survive in Laos as a falang, a foreigner, you had to know what to avoid and what was safe. All evils were waterborne, which meant that anything having touched water that had not been boiled was suspect. Fruit, lettuce, ice cubes, all to be avoided without knowing the preparation process. Your body became an unwilling host to a foreign invader. And then you basically shit or puke your insides out. Simple.

The Air America Club in Pakse was a dark, air-conditioned oasis in a place known for high humidity, high temperatures, and unforgiving crotch rot, it was full of cold drinks of all kinds (beer, Coke, 7-up) and fast food (burgers, tuna sandwiches, more burgers, hot dogs, and grilled cheese) typically found at the end of the 9th hole in most 18 hole golf courses. The staff was top-notch.

Bob had put the word out to Air America dispatch to find me a hop back up to Savanakkhet that day. Failing that, someone would find me a place to sleep for the night. With the amount of traffic going back up north, I was going to find a ride. I was not panicked. I was headed back north today.

There were all types in the Air America Club: CIA officers, Air America pilots, Lao/Thai/Filipino pilots and aircrew, and rice kickers, people who would kick pallets of rice off the back of C-123s and C-46s (the sides of) all showed up to talk and catch up. You could hear Lao, Thai (which was damn close to Lao), snippets of French, American, some Cantonese, but no Vietnamese. Not yet anyway.

Sometimes a Raven or two might make an appearance, though they were never there.

Raven Forward Air Controllers (FACs) were young US Air Force officers who did not exist in Laos, though their mission involved flying a Cessna armed with smoke rockets and the Raven’s personal sidearm, if he was carrying. If they died in Laos, a Raven’s death was quickly documented to have occurred in Thailand. They were as insane as people got in 1972. I visited their BAQ, their quarters. A skull in a pith helmet sat on the bar in the common area, greeting you.

Your one engine Cessna may have cratered on the side of that craggy hill you never saw come up at you through the fog on the Lao side of the Cambodian border, but you died in Utapao, Thailand, driving drunk or something or other. Blunt force trauma was a favorite of the Thai coroner. Ravens needed to eat and the Air America Club was the safest place in Pakse.

Pakse was located in the south of Laos, north of Cambodia, and west of Vietnam – which was called South Vietnam then. The Ho Chi Minh trail made its way down to the Mekong delta on the Lao/Vietnam border. Americans spent millions trying to stem the traffic making its way south. The North Vietnamese Army (NVA) knew how to move goods south, and the B52 strikes became an annoyance and just something to deal with, as much of the environment as the monsoon rains.

There were no roads to speak of but the Ho Chi Minh Trail and some feeder roads going into the wilderness. The purpose of the American air presence in Thailand and Laos was primarily traffic interdiction on the Ho Chi Minh trail meaning that the purpose of the American air presence was to bomb the living shit out of the trail.

The Americans succeeded in dropping bombs, but little else. Arms, people, and materiel flowed south, abated here and there, but never stopped for long. Lima bases around Pakse provided navigational beacons to the air traffic dumping its harvest on the general area on and around the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Air America helped keep the Lima bases supplied and operational.

It was only one year before Laos fell, or rather, was absorbed, by the borg, the Communist group known as the Pathet Lao, Lao Homeland. It was two years before it all went to hell and Saigon officially became Ho Chi Minh City, but cities like Vientiane were much more sedate than Phnom Penh in Cambodia. There was an easy escape to Nong Khai across the Mekong in Thailand by pirogue. There were just fewer people in Laos.

Many considered urban Laos safe for civilians. At the time it still was. The issue was that none of us were civilians anymore.

I was catching up on baseball scores reading the Stars and Stripes, the major source of American news available. Even stale, news was still news. I was reading the box scores thoroughly while finishing my French fries, trying to kill time.

Bob, the Sikorsky pilot, walked up to the table.

“Hey, want to go on a mission? Rumor has it we are going to Lima Eleven.”

A mission? Me?

“Hell, yes. Let’s go.”

PKZ to Lima 11 and back

And this is where things could have gone wrong. Getting asked to go on a mission. I’m not sure I understood what he really meant, but I had a lot of time to kill in a very dull place. I wasn’t about to go into Pakse to sightsee. My primary objective now was to find a flight north.

I did not comprehend either the gravity or the insignificance of that question while I was in the moment. All I know was that I had time to kill, and why not?

“Can you get me out of here today?”

“Sure. Sal checked with Dispatch. He thinks there’s a Porter headed back north later. You got time for us.”

The Pilatus Porter was what was called a Short Take Off and Landing (STOL) aircraft. A Swiss-engineered single-engine plane, it could take off and land with very little to no runway. It was also solidly built — the plane knew how to take bullets and land on a postage stamp. Pilots loved it. I’d never been in one.

“Sure,” I said, my heart rate climbing.

“Onward, then,” said Bob.

We walked out onto the hot tarmac. A bit of the tar had started to bubble through the steel grates as the morning ripened. It was that kind of day in southern Laos. If you didn’t like humid and hot, you could always opt for hot and humid.

I jumped into the Sikorsky and strapped in, ready to go on one more helicopter ride.

A Lao soldier with a gun slung over his shoulder hopped in after placing a transmitter/radio set of some sort on the floor of the helicopter’s passenger cabin. We made eye contact and that’s about it. I got to wear a crew helmet. He did not.

The mission was simple. We were to take the soldier to an outpost, drop him off, and come back. We’re in Laos in a war zone, what could happen? I did not stress it. Not then.

We took off quickly and went due east. Bob was giving it the gas, sacrificing speed for altitude. We gained speed as we leveled off our altitude until we had hit our cruising speed as we made our way towards the line of mountains and clouds fast approaching.

It would be a cop-out to say the scenery outside was just like Apocalypse Now, but it was — we were on a mission. Of course, the movie wasn’t out yet . . . details. The fog came up out of nowhere and only to disappear back into its fog hole just as quickly. I was not flying the helicopter, so I was not in control of the situation nor the aircraft, all I could do is experience it in awe of it being incredible and unattainable. Had I tried to achieve this moment, I never would have. I never could have.

My cabin mate seemed quite happy getting back to what he was getting back to. The lot of a soldier in any war can’t be good and Laos 1973 could not have been different. He weathered better than his clothes. It was impossible for clothes and fabric to survive the Lao weather. Too hot. Too humid. No escape. Anything green was assumed to be a uniform.

A sheer granite cliff materialized outside the open cabin door, maybe sixty yards away, amazing in both majesty, breadth, and yosemiteness. It threatened the helicopter, beckoning us like a big granite magnet.

It had to be Lima 11, our destination. The site wasn’t much, but its location was key — it looked over much of the Bolovens Plateau, a waypoint perched between civilization and the Ho Chi Minh trail.

American aircraft, F-4, F-111s, Skyraiders, Wild Weasels, B-52s, C-130s armed to the teeth into Puffs – flying gunships spewing molten hell through flesh and bone — all needed a way to get there. The transmitter at Lima 11 gave it to them.

We scaled the cliff, chugging up it, warm air buffeting us again like we were in autorotation (but going up), cradling us away from the rock. We made it to the top and skootched over to alight on some cleared dirt. The soldier, bid his goodbye and jumped out of the helicopter, Enfield slung over his shoulder.

Without a word, we were off and dropping back into Pakse airspace again. On landing, we parked and it dawned on me that I had completed a mission. Once Bob and Sal had powered down the Sikorsky, Sal let me know that Dispatch had called in and that my ride north was due to leave in thirty minutes or so.

I thanked each, shook their hands, went back to the Club, and ordered a Coke – cold, no ice, for a quarter. Twenty minutes later, the Porter pilot walked into the club to collect me.

I walked with him back to the tarmac. It was starting to cool down. It did not smell like rain. We were in the dry season.

PKZ to ZVK

The flight back to Savannakhet from Pakse was uneventful. I was packed into a Pilatus Porter with a high-ranking Lao officer, his adjutant or aide, and his two “daughters.” Strapping into my seat, I could smell daughters’ makeup and see their perfume in the Porter’s surprisingly large cabin. We all faced each other in a bench arrangement.

I’m not sure they wore enough perfume to offset the adolescent sweat I had been excreting all day, but the ladies in the Porter did their best to mask it.

I fell asleep listening to the drone of the turboprop. We landed as the sun set. The scent of edible air, rotting organic matter, and AV fuel hit me coming off the plane.

My Father was there. He knew. He always knew.

“Hi, Pop. Here’s $12.50 from the twenty you gave me.”

“Keep the change. You may need it tomorrow.”

Excellent writing sir. I lived in Vientiane Laos for two years (1967-69) when I was 8 to 10 years old and I flew to Udorn several times with my dad who was working for the DIA and posing as an assistant air attache assigned to the US embassy. We went to Savanakhet and Pakse but I don’t remember those trips like I remember the ones into northern Thailand. Dad received 23 Oak Leaf clusters accompanying the Air Medal for his flying time in Southeast Asia during those two years. Dad was the first USAF pilot to log 1000 hrs in the F106 Delta Dart fighter interceptor in the early 1960s.

Pierre! I remember you as a classmate at ASV. Your writing here is probably the best description of the unreality of life in Laos at that time. Your trip to Savannakhet reminds me of the trip I made there with Hubert (around the same time).

I am so glad you wrote this!

Well interesting, I thought my summer spent working on a lake freighter as a deckhand at age 16, 7 months after the Edmond Fitzgerald went down was interesting but you win hands down. What a snap shot in time amazing.

Great writing. I was in Laos 70 to 75. Couple of years behind you in school, but I remember you. Reading this gives me fond memories of my experiences. Also enjoy hearing about the places I didn’t make it to and different experiences others had there. Thank you